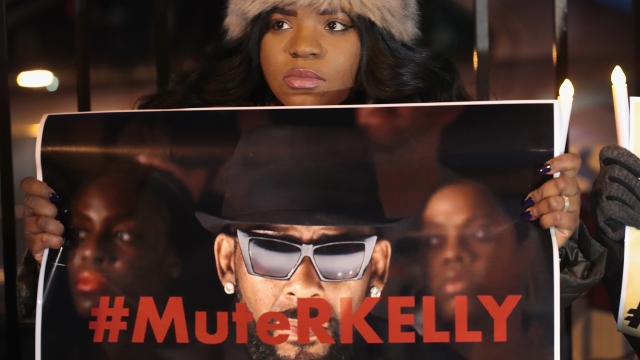

Since 1996, numerous women have accused singer R. Kelly of sexual assault. But many of their claims have fallen on deaf ears because of who the accusers happen to be: black women. Just listen to what people had to say about them in the Lifetime docuseries "Surviving R. Kelly":

"When I first met those girls, I judged them. Not him."

"Maybe I didn't care because I didn't value the accusers' stories — because they were black women."

"I just didn't believe them."

That gentleman was a member of the jury that acquitted R. Kelly in 2008 on charges of child pornography.

This raises a question: In the #MeToo era, when the voices of many sexual assault survivors are being amplified, why are the stories of some black women being dismissed?

"The stories that are being told in the docuseries are very common and familiar stories that are experienced by a lot of the women that I work with."

"This is really just putting a spotlight on these issues that are highly prevalent among black women and children."

Dr. Inger Burnett-Zeigler is a clinical psychologist who researches mental health in the black community. She points out the damaging stereotypes of black women that impact how they're viewed.

"This idea that young black girls should know better, or that they bring it on themselves. And some of that is due … to the fact that black women are seen as being more sexualized or more promiscuous."

That's not just an anecdote. A study by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality found that adults perceived black girls to be less innocent and more familiar with sex than white girls the same age as them.

"And because of that, there's this idea that since they should have known better, they kind of knew what they were getting into, by walking into this situation."

"I hear stories of women that were abused by people in the neighborhood that said, you know, 'well, you were being fast, or you dressed in this or that way?' Or, 'What did you expect to happen if you went over to such and such's house alone?'"

That tendency to blame the victim might have informed the juror we heard earlier: "I just didn't believe them, the women. I know it sounds ridiculous. The way they dress, the way they act — I didn't like them."

Burnett-Zeigler says the issues that have led others to discount the pain of black women doesn't just stem from how others view them, but also how they view themselves.

"I think that we often don't see the pain of black women. I think that we — and I can speak both personally and professionally — have been kind of conditioned to suppress our pain. I think we also kind of play into this stereotype that we can handle it all. And so you know, when somebody does express some sort of pain or distress, we default to this idea of you can deal with it, you're tough, you're strong. And so when someone does express it, it's easy to minimize it in that way."

The docuseries has prompted other survivors of sexual assault to speak out. The National Sexual Assault Hotline reported a 27 percent increase in calls after the series premiere.

"I'm here today to encourage victims of sexual assault or domestic violence related to these allegations to please get in touch with our office."

If other assault survivors do choose to come forward, Burnett-Zeigler suggests applying a level of understanding that women featured in the docuseries weren't afforded.

"I would just really want to underscore empathy towards not only young women, but women in general, and encourage kind of a broader understanding of what that woman is coming into this vulnerable situation with that may make it more likely for her to be harmed in the long run."