While COVID-19 lands more people in hospitals, doctors are turning to monoclonal antibodies to help keep people out. Now some states are finding new ways to provide more access to them.

Governor Greg Abbott was one of the latest political leaders to test positive, his office confirming he received monoclonal antibody treatment this month.

They were already used for the treatment of other illnesses, but when the pandemic started companies developed them to fight the coronavirus.

"The biotechnology industry figured out how to use those to basically make targeted missiles toward molecules that were causing problems," said Dr. Kami Kim.

Dr. Kim has been involved in their trials since the early days of the pandemic, as an attending physician at Tampa General Hospital and the director of the Division of Infectious Disease and International Medicine at USF Health. Dr. Kim explained researchers learned a key was giving them early on.

"The spike protein is the business end of the virus that allows it to get into human cells. And so these antibodies are called neutralizing antibodies because they neutralize the virus. And so if you give these antibodies early on you can prevent the virus from getting into your cells," said Dr. Kim.

The goal is to prevent disease progression, though it's not a substitute for a vaccine.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization to Regeneron, Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline. The distribution of Lilly's product is paused, however. The EUA's authorize treatment for mild-moderate disease in those 12 and older, who test positive and are at risk of progressing to severe illness.

"Right now there’s a fair amount of provider discretion into who gets the antibodies. We start out obviously with the highest risk patients but you know there are a lot of people who have medical problems who would want the treatment and given the fact that our hospitals are overrun and we know it’s beneficial, it's pretty much loosened up so that you know most people who want the drug if they present early enough in their disease can get it," said Dr. Kim.

The Ankroms turned to the treatment in Florida when the virus hit their family.

"I felt like I could feel every nerve and every tooth, my whole body ached, it was unreal," said Lydia Ankrom.

Lydia said it wasn't until she talked to a friend she learned about monoclonal antibodies. She called the treatment a

game-changer in her case.

"I'm telling you, I could not believe the difference in the way that I felt 24 hours later, it was day and not," she said.

However, Lydia said her husband was a different story.

"One night he was coughing so bad and my 3-year-old Lily said to me, you know is daddy going to get better? And in my mind I thought if I take him to the hospital he's going to be alone, and is he going to come out?" Lydia said.

At the time of his illness, Lydia said he was not able to access the treatment.

"This week when I listened to my husband cough I thought to myself I wonder what his long term problems are going to be. And I guess we'll only know as we go. I mean we're all learning about this as we go but I can tell you I'm extremely thankful I was able to have that," Lydia said.

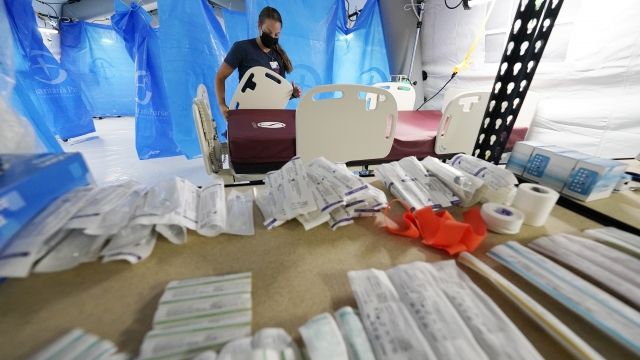

States are now finding new ways to increase access to the treatment. Florida said it's developing strike teams for long-term care facilities and setting up monoclonal antibody sites across the state.

"This is helping relieve some of the pressure because I know they're doing a lot in these health systems. So this is supplementing that and we'll expand as needed," Governor Ron DeSantis said during a news conference.

Texas said it's setting up regional infusion centers in major cities.

At least one pharmacy in Arkansas, West Side Pharmacy in Benton, has set up an infusion site.

The Arkansas Department of Health is seeing if it's a viable model to administer through pharmacies.

"The rural areas of Arkansas, we have health care provider shortages and we may not have a hospital with a clinic that could give an infusion or even just a medical clinic that's nearby that could give an infusion, but many small towns do have pharmacies and if it could be administered appropriately in that setting that would make the monoclonal antibodies much more available to people who really need them," said Dr. Jennifer Dillaha, the chief medical officer for the Arkansas Department of Health.

HHS said it's reaching out to states to help in expanding access to treatments. The agency said it's seen a significant increase in ordering of monoclonal antibodies, with about 78 percent dominated by regions with low vaccination rates. It's currently shipping about 120,000 patient courses a week.

There's no cost to the patient in most cases for the product itself, but there can be costs for its administration, though those can vary based on insurance and facility.

The National Infusion Center Association created a locator for COVID-19 antibody therapy.

Meanwhile, the Lydia Ankrom is hopeful to see more access.

"If we know these antibodies save people's lives, I think we ought to be doing everything we can to get them out there," she said.