"I'm pregnant. So it was like, before, people were questioning if I was even having sex, or like, 'Is that a thing for people with disabilities?' And I had to say, 'Yeah, it's a thing. It happens,'" Brittany King said.

"How is your pregnancy been so far?" Newsy's Melissa Prax asked.

"Everything's fine. I find out the sex on Thursday. So I'm excited for that," King said.

"There's this whole idea of because I had a stroke, the idea of pushing out a baby might be a little strenuous for me. And the condition that I have might bring about another stroke. ... So they've been monitoring, seeing me more frequently than the average pregnant woman," King said.

In the U.S., there are over 1 million women with disabilities that are of childbearing age. Up until this point, there's been little data released on women with disabilities and their pregnancies.

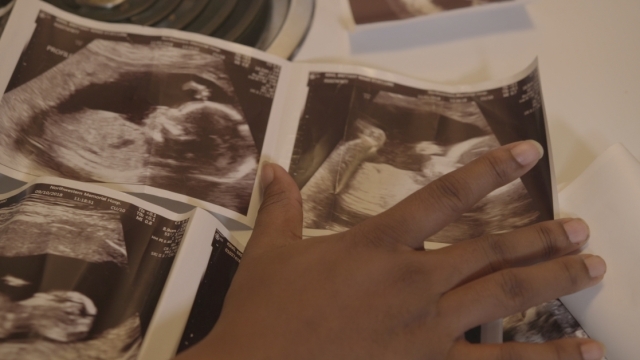

"We got to hear the heart rate early on. We got to see the flashing flicker with the first ultrasound. Then to go from like, sight to sound was really cool. Her heart rate is quick. And mine is, because I have sickle cell, so it's like she's in a race with me. Sometimes I was like, OK, so when I calm down, she calms down. And then when I'm active, she's active. So that's maybe the most discomfort is that when I'm walking around, maybe, like, down a hallway, she'll start and reposition herself. And it's like, 'Can we move one at a time?'"

"Tell me a little bit about some of the considerations that, you know, you as a woman with a disability are preparing for as being a mother?" Newsy's Melissa Prax asked.

"They're trying to figure out the birthing method. Because I have damage from the stroke, they don't know if pushing would be a little too stressful, or should they just go to straight C-section," King said.

"Are you scared at all to give birth?" Prax asked.

"I'm not. I feel like it's going to be easy, for whatever reason. Maybe because there wasn't any complications with her up to this point. So I think it's just going to be she's gonna slip and slide out. That's my hope," King said.

"Women are supposed to carry the baby, so disabled, non-disabled, your body's going to do what it needs to do," King said.

"I think the most misinformed fact is that, 'Oh, because people with disabilities are reproducing we'll have more people with disabilities.' But it's not a thing, because ... my disability happened while I was in college. … How you get disabled is not a product of two disabled people having a baby," King said.

"Once a week we're doing NST — so that's 'no stress test'. So they kind of just let me hang out in the chair for 20 minutes and test, like, the motion and heart rate of baby," King said.

"In high-risk pregnancies, it may be necessary to incorporate input from a different specialist, it may be important to get additional screening for the baby, it may be necessary to get additional screening for mom, making plans, scheduling her induction at a time when it's most feasible for the pediatrician who may need to do surgery on this baby at the time of delivery, or feasible for a time when the correct surgeons are going to be the hospital who are able to accommodate that particular patient. ... Our high-risk patients fall into three categories. Sometimes moms are high-risk because they have long-standing chronic conditions. … Then we have women who come to our office because their babies have high-risk issues. So perhaps they were on an ultrasound and notice an anomaly, they get referred to us. ... And then finally, patients who were our patients for prior pregnancies, they come back to us because of those relationships," said Dr. LaTasha Nelson, a maternal fetal physician at Northwestern Medical Group.

Research, including a national survey from the Baylor College of Medicine, shows women with disabilities face barriers in getting the same level of medical care as women without disabilities — even though they were more likely to see medical providers in the first place. This is especially true when it comes to reproductive care. Women with disabilities found it harder to get cancer screenings or access to birth control. Women with disabilities in the survey also said it was hard to find medical providers who would see them throughout their pregnancy.

"At the end of the day, we have to understand that these women who have disabilities are still women who are pregnant, and you can't get blinded by whatever else is going on, so that you can allow them to enjoy the pregnancy, because that's the exciting part," Nelson said.

"So how do you think you're going to feel when you get your baby?" Prax asked.

"I think I might cry, actually. Because I'm not really a sensitive person, but seeing this thing that's been growing in me and making those ... movements, I think I might cry," King said.

"I know a lot of people, when they're pregnant, crave interesting combinations. Is there anything that you have craved?" Prax asked.

"It was pickles at first, and then it was steak and chicken. And now onto ravioli," King answered.

"What would you want people to know about mothers with disabilities and women with disabilities carrying biologically carrying a child?" Prax asked.

King said: "I want them to know that it's not any different from any other person who carries a child, except that there may be limitations. So I might have to sit down a few more times per day or decide when it's time to just go to sleep, because I might be more fatigued than usual. But I'll think that's not different from 'normal' pregnancies."